Getting Folksy

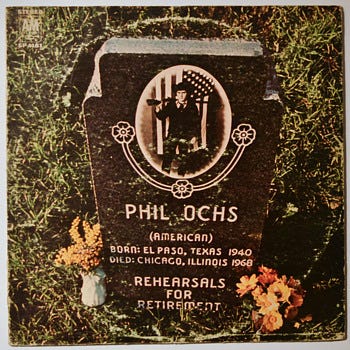

The singer-songwriters of the 60’s alt-folk era grabbed me by the ears. The music appealed to my conscience. While McCartney and Lennon wrote love songs, Phil Ochs wrote about the harmfully complacent bourgeoisie with “Outside of a Small Circle of Friends”. Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler offered up “The Ballad of the Green Berets” while Buffy Sainte-Marie protested all war as “The Universal Soldier”. On AM it was “Sunny”, but on FM “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall”. These words commanded my attention and demanded action.

This music, that I was exposed to at the formative age of 13, helped me culturally leapfrog over boys who were more impressed by Corvettes, cool clothes, and hot girls. It happened one morning in 1965. I flipped my clock radio from AM to FM. I moved around the dial passing NPR, jazz, and foreign language stations. I stopped when I arrived at a sound I’d never heard. It was the screaming guitar of Jimi Hendrix wailing through “Purple Haze”. It was immediately followed by Judy Collins rendition of “Suzanne” by Leonard Cohen, then without interruption Country Joe and the Fish with “Feel Like I’m Fixing to Die Rag” (Gimme an “f”).

KMPX-FM 106.9 ushered in a catalogue of folk, rock, folk-rock, blues, experimental sound smiths like Beaver and Krause and international artists like Miriam Makeba, all absent on the AM band. FM changed my music buying habits from singles to albums. When I purchased “East-West” by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, it was to listen to several cuts I’d heard on FM. The jocks on KMPX were my blues ambassadors. When I heard Mike Bloomfield’s hypnotic guitar solos, I wanted more. I went to see Bo Diddley, Albert King, B. B. King, John Lee Hooker, and others all imported by Bay Area rock impresario/hero, Bill Graham.

While FM radio sated the rabid appetite for new and newly discovered artists, it also moonlighted as a bullhorn for the protest movement. Along with a steady diet of blues and rock I tasted samples of Tom Paxton, Joan Baez, and Tim Hardin. I digested civil rights abuse, international conflicts, and our own involvement in unjust wars. I was invited to engage in a movement to help to free all people, and to purge ourselves of us those who would seek to control us for personal gain: the racist despots, the dirty politicians and the corporate overlords who bought them.

I grew my hair as long as my Catholic school would allow before I got sent home. I doffed my wide wale cords and paisley shirts and marched to the Fillmore Auditorium or the Avalon Ballroom and pledged my fealty to psychedelic pacifism. A screaming guitar was my siren’s song. I was lured into an investigation of American culture, and, for the first time, I analyzed and criticized what I saw, read, and heard. I listened more to the oracles: Tim Buckley, Eric Andersen, and Bob Dylan.

I vowed to fight for peace, hanging on every verse. Variety shows and late-night fare exposed these artists to new audiences. It seemed, however, incongruous to me when a protest singer appeared on a show sponsored by an oil company. These compositions were meant to inspire the working proletariat, not just entertain. You can’t be anti-war when one of your sponsors is the US Army. It was evident that, as poet Gil Scott Heron would articulate two years before we pulled out of Vietnam in 1971 with his “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.”

This was not a conspiracy theory. This was not a cult. This was not Q-Anon. This was consciousness. It was a dare to be concerned; not just to be entertained but engaged. Take to the streets. Make your voice heard. Young men are being sent to die at the whim of lying politicians and hawkish military commanders. Show up, stand up or sit in. Make a difference.

As a kid, I was powerless, but I felt part of something. It spoke to me. I allowed no political opinion without examination. I recognized what George Wallace, Strom Thurmond, and Lester Maddox were all about. I sided with the we and not the I. I decried capitalism. I determined that a social democracy was fairer. I wished for universal health care while Reagan shut down the mental hospitals. I ran from the Alameda County Tac Squad in Berkeley as I protested our presence in Cambodia. I tuned in, but I didn’t drop out. Too much was at stake.

It was a testament to their character that these folk artists sought to get their music noticed. They called upon their talent to help us see. I wish we had them now. Man, do we need them.